Introduction

I hope this introduction serves well for anyone who needs a refresher about Operating systems in general, or people who wants to know how a Linux/Unix system works under the hood, after all the Cloud is made of Unix/Linux systems (huge part of it). Memory management is a complex subject, and I declared myself a rookie in the sense about how the Linux kernel works, however I will try to include as much details as I can possible explain or understand.

Take a deep breath because it’s going to be a long ride

Why do we even need memory?

On brendan’s book[2], the introduction to Chapter 7 says:

System main memory stores application and kernel instructions, their working data, and file system caches. In many systems, the secondary storage for this data is the primary storage devices (disks), which operate orders of magnitude mode slowly.

the reason is because the CPU needs to execute a set of instructions which are copied from a storage device (hard drive) to the main memory aka RAM and here the fetch-decode-executecycle shows up. If you want to learn more about it watch this video and follow-up with this article. At this point you know why memory is needed. Before introducing the next topic I would like to quote what Linus[4] wrote on his thesis a while ago, in regards of the memory management process:

Memory is one of the most fundamental resources in the system, and as such the performance of the memory management layer is critical to the system. Making memory management efficient is thus of primary importance: not only do the routines have to be fast, they have to be clever too, sharing physical pages aggressively in order to get the most out of a system.

furthermore…

However, to make matters even worse, memory management is typically one of the areas where there are absolutely no hardware standards, and different CPU’s use very different means of mapping virtual addresses into physical memory pages. As such, memory management is one area where traditionally most of the code has been very architecture-dependent, and only very little high-level code has been shared across architectures even though we would like to share a lot more.

As a reminder, back in the 90’s, Linus starting working on the kernel on the Intel-80386:

The original Linux was not only extremely PC-centric, it wallowed in features available on PC’s and was totally unconcerned with most portability issues other than at a user level. The original Intel 80386 architecture that Linux was written for is perhaps the example of current CISC design, and has high-level support for features other current CPU’s would not even dream about implementing (see for example [CG87]).

Linus mentioned on his thesis that everything related to memory management belongs under the directory mm/, from the following paragraph:

The basic Linux kernel is directly organized around the primary services it provides: process handling, memory management, file system management, network access and the drivers for the hardware. These areas correspond to the kernel source directories kernel, mm, fs, net and drivers respectively.

but also, in The magic Garden explained[3], Chapter 3, it’s been stated that:

A major concern for any operating system is the method by which it manages a process given the restrictions imposed by the amount of physical memory installed in the computer hardware. It must be determined where the process will be placed in main memory, and how memory is allocated to it as it grows and shrinks during its execution. One problem that is familiar to all operating systems is what do when memory is scarce.

To overcome these and other memory management problems, UNIX System V Release 4 has adopted a concept of virtual memory (Moran 1988).

Physical Memory

Physical memory is what we know as RAM (Random Access Memory), and is found on the memory bank of your laptop or more commonly servers. Most of servers out there are NUMA (Non-Uniform memory access) at this point in time but UMA used to be the rule. The main difference in UMA there is a single shared BUS that connects the memory controller with the CPU and the other components. Whereas in NUMA, each CPU has its own internal connection with the memory controller. To easily understand the difference see the following diagram:

Each memory bank inside the kernel is known as a Node (in my case node0). In NUMA systems, and each processor can access a different node, which is known as the distance (this has a cost associated in terms of latency, since accessing the CPUs local node is faster than a remote node). Nodes are known inside the kernel as type pg_data_t.

A node is divided into different Zones which represent different ranges of memory. On the x86 the zones are:

- ZONE_DMA (first 16MB)

- ZONE_NORMAL (Between 16MB and 896MB, this is where many kernel operations happen and is the most critical zone)

- ZONE_HIGHMEM (Between 896MB - END)

Zones are declared in the include/linux/mmzone.h file, they as declared as struct zone. checking my laptop I noticed the following:

$ cat /proc/pagetypeinfo

Page block order: 9

Pages per block: 512

Free pages count per migrate type at order 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Node 0, zone DMA, type Unmovable 1 1 1 0 2 1 1 0 1 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA, type Movable 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 3

Node 0, zone DMA, type Reclaimable 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA, type HighAtomic 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA, type CMA 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA, type Isolate 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA32, type Unmovable 838 384 65 16 9 2 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA32, type Movable 26195 10502 648 146 20 4 0 1 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA32, type Reclaimable 506 657 590 404 188 82 20 13 2 1 0

Node 0, zone DMA32, type HighAtomic 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA32, type CMA 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA32, type Isolate 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone Normal, type Unmovable 440 357 227 72 38 6 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone Normal, type Movable 11803 2752 730 78 15 11 3 2 2 0 0

Node 0, zone Normal, type Reclaimable 0 38 33 16 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone Normal, type HighAtomic 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone Normal, type CMA 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone Normal, type Isolate 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Number of blocks type Unmovable Movable Reclaimable HighAtomic CMA Isolate

Node 0, zone DMA 1 7 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA32 25 1359 144 0 0 0

Node 0, zone Normal 122 2039 155 0 0 0

DMA32 zone only exists under x86_64 systems, the ZONE_HIGHMEM is created only in 32 bits. The reason for it is found on the source code actually:

enum zone_type {

/*

* ZONE_DMA and ZONE_DMA32 are used when there are peripherals not able

* to DMA to all of the addressable memory (ZONE_NORMAL).

* On architectures where this area covers the whole 32 bit address

* space ZONE_DMA32 is used. ZONE_DMA is left for the ones with smaller

* DMA addressing constraints. This distinction is important as a 32bit

* DMA mask is assumed when ZONE_DMA32 is defined. Some 64-bit

* platforms may need both zones as they support peripherals with

* different DMA addressing limitations.

*

* Some examples:

*

* - i386 and x86_64 have a fixed 16M ZONE_DMA and ZONE_DMA32 for the

* rest of the lower 4G.

*

* - arm only uses ZONE_DMA, the size, up to 4G, may vary depending on

* the specific device.

*

* - arm64 has a fixed 1G ZONE_DMA and ZONE_DMA32 for the rest of the

* lower 4G.

*

* - powerpc only uses ZONE_DMA, the size, up to 2G, may vary

* depending on the specific device.

*

* - s390 uses ZONE_DMA fixed to the lower 2G.

*

* - ia64 and riscv only use ZONE_DMA32.

*

* - parisc uses neither.

*/

...

#ifdef CONFIG_HIGHMEM

/*

* A memory area that is only addressable by the kernel through

* mapping portions into its own address space. This is for example

* used by i386 to allow the kernel to address the memory beyond

* 900MB. The kernel will set up special mappings (page

* table entries on i386) for each page that the kernel needs to

* access.

*/

Each physical page in the system has a page struct, which is declared in the include/linux/mm_types.h file and is probably the most important structure in regards of memory management.

Virtual Memory

Brendan’s book mentioned this briefly, and after getting that reference from Peter J. Denning:

The designers of the Atlas computer at the University of Manchester invented virtual memory in the

1950sto eliminate a looming programming problem: planning and scheduling data transfers between main and secondary memory and recompiling programs for each change of size of main memory.

Imagine you were in the 1970s-1980s and processors like the Intel 8080 only provided an address space of 64kbytes (you may have in your laptop at least 8192000 / 8GB RAM), but back those days processors used direct physical memory address to access code and data. There is something in particular mentioned in the book, programmers had to arrange that the program code and data avoided any holes in the given address space. It is much convenient to ignore the physical layout of a machine’s memory and work instead with an idealised or virtual machine. A program/process can then reference the virtual memory addresses for both code and data and a hole in memory can be ignored since the restrictions imposed by physical memory are invisible to both the program and programmer.

A virtual address schema gives the illussion that there is more memory available than is physically installed in the machine. This allows the OS to run a program that is larger than physical memory, however a program reside in physical memory and it must generate real addresses for both its code and data. Therefore, a translation mecanism is needed to convert virtual memory to physical memory addresses at run time and must not provide any significant overhead.

From the previous quote, it is referring to the Memory Management Unit / MMU. Translation Lookaside Buffer or TLB, is a memory cache use to reduce the time taken to access a memory location and it stores the recent translations of virtual memory to physical memory.

A process address space has its own virtual address space, which of course is mapped to physical memory by the operating system (main memory and swap, if exists). Another important definition to remember is a page. A page is a unit of memory, historically has been 4kb or 8kb but depends of the architecture, and its how the physical memory has been divided (also known as page frames). The selection of the size is defined when the kernel is built. On the latest Ubuntu 19.10 release the page size is still set to 4k:

$root@testing:~# uname -r

5.3.0-26-generic

$root@testing:~# getconf PAGE_SIZE

4096

For now, consider the following example (From the awesome “Writing an OS in Rust”), running the same process twice in parallel:

Here the same program runs twice, but with different translation functions. The first instance has an segment offset of 100, so that its virtual addresses 0–150 are translated to the physical addresses 100–250. The second instance has offset 300, which translates its virtual addresses 0–150 to physical addresses 300–450. This allows both programs to run the same code and use the same virtual addresses without interfering with each other.

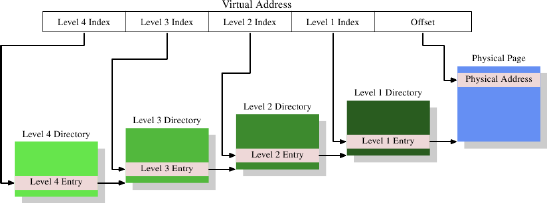

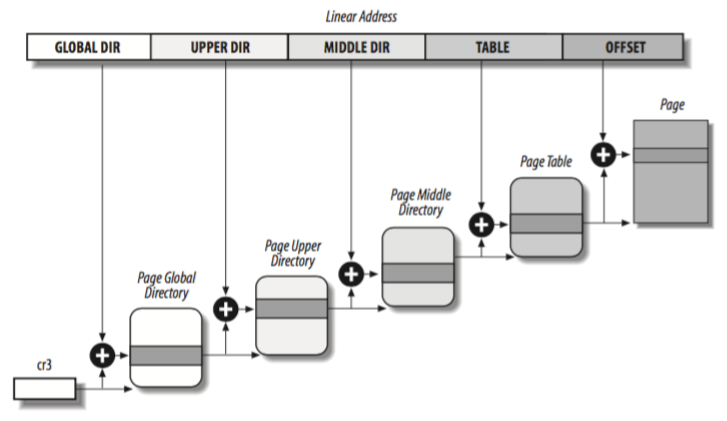

The virtual address space is implemented and handled in the Memory Management Unit by the processor and its by process. The OS needs to fill out the page table data (by each process) every time the process is loaded, this is a another feature implemented in the CPU (cr3 register). When a process its in CPU, loads the page table data from the highest hierarchy level (multi level pages) aka level 4 (this is also known as Page Global Directory, Page Upper Directory, Page Middle Directory and Page Table).

The page table data structure then is composed as:

The virtual address is, in this example, split into at least five parts. Four of these parts are indexes into the various directories. The level 4 directory is referenced using the

cr3register in the CPU. The content of the level 4 to level 2 directories is a reference to next lower level directory. If a directory entry is marked empty it obviously need not point to any lower directory. This way the page table tree can be sparse and compact. The entries of the level 1 directory are partial physical addresses, plus auxiliary data like access permissions.

The CPU takes the index part of the virtual address corresponding to this directory and uses that index to pick the appropriate entry. This entry is the address of the next directory, which is indexed using the next part of the virtual address. This process continues until it reaches the level 1 directory, at which point the value of the directory entry is the high part of the physical address. The physical address is completed by adding the page offset bits from the virtual address. This process is called page tree walking. Some processors (like x86 and x86-64) perform this operation in hardware, others need assistance from the OS.

Pages are commonly 4k size as seen before, and each page table can have up to 512 entries, each entry is 8b (512 * 8 = 4096bytes or 4k - it fits exactly in one page), page tables are also stored in memory.

Now in Kernel 5.5 and beyond, after this commit, 5 level paging is enabled by default.

Segmentation

One of the main tasks of the operating system is to isolate a process from each other, so in order to achieve this the system uses hardware capability to protect memory areas. The approach differs from hardware and the implementation on the OS. On x86, the two ways to protect memory are segmentation and paging.

The support for segmentation has been removed on x86 for 64 bits and this concept applies mostly in legacy systems aka 32 bits.

Fragmentation

This is more clear after reviewing the following case:

There is no way to map the third instance of the program to virtual memory without overlapping, even though there is more than enough free memory available. The problem is that we need

continuous memoryand can’t use the small free chunks. One way to combat this fragmentation is to pause execution, move the used parts of the memory closer together, update the translation, and then resume execution:

The disadvantage of this defragmentation process is that is needs to copy large amounts of memory which decreases performance. It also needs to be done regularly before the memory becomes too fragmented. This makes performance unpredictable, since programs are paused at random times and might become unresponsive. The fragmentation problem is one of the reasons that segmentation is no longer used by most systems. In fact, segmentation is not even supported in 64-bit mode on x86 anymore. Instead paging is used, which completely avoids the fragmentation problem.

Paging

The idea is to divide both the virtual and the physical memory space into small, fixed-size blocks. The blocks of the virtual memory space are called pages and the blocks of the physical address space are called frames (page frames). Each page can be individually mapped to a frame, which makes it possible to split larger memory regions across non-continuous physical frames.

The advantage of this becomes visible if we recap the example of the fragmented memory space, but use paging instead of segmentation this time:

In this example we have a page size of 50 bytes, which means that each of our memory regions is split across three pages. Each page is mapped to a frame individually, so a continuous virtual memory region can be mapped to non-continuous physical frames. This allows us to start the third instance of the program without performing any defragmentation before.

As mentioned before, 32 bits architecture implement a two page level, while 64 bits implements a four levels, although this has been implemented since kernel version 2.6.11. The current levels are:

- Page Global Directory: Highest level in the hierarchy and includes addresses from the Upper Directory.

- Page Upper Directory: Points to the addresses from the Middle Directory.

- Page Middle Directory: Points to the addresses from Page Table

- Page Table: Points to the physical addresses (page frame)

On 32 bits with no PAE (Physical Address Extension), just two levels are available, otherwise it will use three (Upper and Middle are set with their fields to 0 bits, and are kept in the same order to make the code compatible for both 32/64 bits). In addition the number of page entries in those page tables are set to 1 and are mapped to the Page Global Directory.

Each process has it’s own Global Page Directory and Page tables and when a context switch happens, Linux saves the current the value of the cr3 register.

References

- https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/latest/admin-guide/mm/concepts.html#mm-concepts

- Systems Performance in the cloud and enterprise

- The Magic Garden explained

- Linux: A portable operating system by Linus Torvals

- https://www.thegeekstuff.com/2012/02/linux-memory-management/

- https://os.phil-opp.com/paging-introduction/

- https://www.bottomupcs.com/virtual_memory_linux.xhtml

- https://lwn.net/Articles/253361/

- https://www.kernel.org/doc/gorman/html/understand/understand005.html